RCMI NEWS: Interview with Dr. Loyda Meléndez

A new item has been added to the Director's Page - Statements, Articles, and Media:

04/02/2021 05:15 AM EDT

New funding opportunity for Community COVID-19 Testing Info Webinar Tuesday, March 16th at 4:00pm EST

Disseminating Message:

The CDCC will host an informational webinar for potential applicants to the RADx-UP CDCC Community Collaboration Mini-Grant Program next Tuesday, March 16 at 4:00 PM EST. This webinar will provide an overview of RADx-UP, the Coordination and Data Collection Center (CDCC), and the Mini-Grant Program, as well as answer questions about the application process.

The registration link is here: https://duke.zoom.us/meeting/

CDCC RFAs: Community Collaboration Mini-Grants and Rapid Pilots

Last week, we announced two new funding opportunities to expand our important work to increase COVID-19 testing in communities hardest hit by the pandemic. The deadline for application for both opportunities is April 16, 2021. Application instructions and a communication kit to spread the word about these opportunities throughout your networks are available at https://radx-up.org/apply-for-

Community Mini-Grants

Community organizations can apply for up to $50,000 in funds to support increased testing for COVID-19 through the RADx-UP Community Collaboration Mini-Grant Program. These funds are available to community-serving organizations, faith-based organizations, community-based clinics, and tribal nations and organizations. Funds can be used to help advance capacity, training, support, and community experience with COVID-19 testing initiatives. This RFA seeks to support the inclusion of additional community partners and stakeholder groups that are not currently part of the RADx-UP program through CDCC sub awards.

Funds can be used to support personnel costs, contracted service costs (transportation, translation, and interpretation, etc.), and non-personnel costs (participant incentives, information and technology equipment, etc.) Please share this opportunity with partners in your community.

Questions? Please contact us at RADx-UP-CDCC@duke.edu .

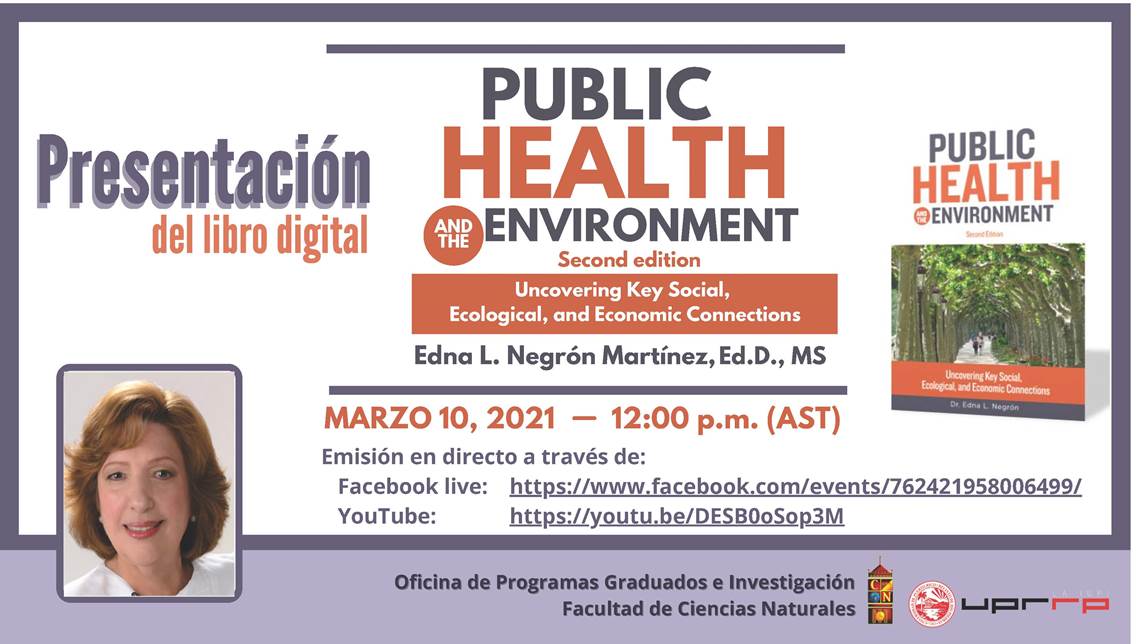

FACEBOOK LIVE: https://www.facebook.com/

YOU TUBE: https://youtu.be/DESB0oSop3M

To end HIV epidemic, we must address health disparities

https://www.nih.gov/news-

02/19/2021 08:45 AM EST

|

|||||||

|